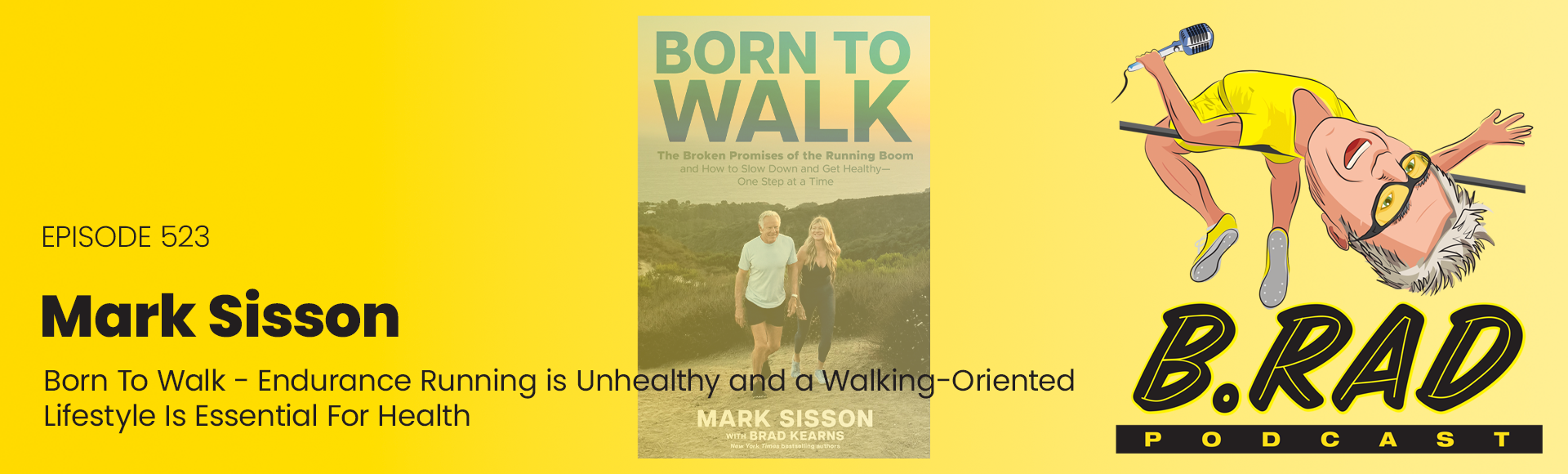

I am joined by Mark Sisson for the wonderful occasion of a new book coming out—Born To Walk.

Tune in to hear us talk all about the book, from the title to what made Mark realize that this story had to be told, what the research about running has actually revealed, and why running is, in many cases, antithetical to good health for a lot of people. You’ll hear us talk about the fascinating research we discovered that supports this idea that humans were born to walk, and while we are able to run (and can run occasionally as a result of walking a lot, sprinting once in a while, lifting heavy things, moving around and moving through space and time), we were not born to run metronomic eight-minute miles every day, day in and day out as some means to achieving some longevity goal or some health goal.

As you will learn in this episode, the running boom of the last 50 years was built upon a House of Cards, and on the idea that humans are born to run. But, humans were not born to run—we were born to walk, and in this episode, you will find out why!

TIMESTAMPS:

We are looking at increasing your longevity through low level aerobic activity. {00:48]

The idea that running was the best route to longevity has been downplayed. [05:56]

Shoes have made big changes in the way people run. With the thick soled running shoes, there has been no decrease in running injuries. [08:03]

Everybody assumes that running is the sort of gold standard of weight loss, of achieving good health, of mental fortitude, and being able to overcome discomfort. [14:32]

What is so appealing about a marathon? [16:47]

There are much kinder, gentler ways to achieve great health, not get injured and support the other things that you’re doing as part of your longevity program. [21:10]

Why doesn’t running and burning calories work in pursuit of reducing excess body fat? [22:27]

There are two kinds of fat. The subcutaneous fat which is simply unpleasant and the visceral fat which is terribly harmful for your health. [24:51]

They promised better results with new cushioned shoes but these shoes have done nothing to decrease injury. [27:21]

Understanding chronic cardio is so important in the endurance scene. You can take a good thing too far. [36:52]

Mark had to change the way he pursued his athletic life.

After retiring from elite competition, how did he learn to train at a lower level? [45:09]

The Ordeal of the Obligate Runner is the title of one of the chapters. What does that mean? [48:31]

What is the difference between being a sugar burner and a fat burner? [56:54]

There is research showing that if you just have a lighter shoe, you save four minutes over a marathon. [01:02:36]

We encourage you to walk but you need to learn the proper form. [01:07:06]

What is the primal approach for getting more energy? You don’t need to run to give yourself immortality [01:18:27]

LINKS:

- Brad Kearns.com

- Brad’s Shopping page

- B.rad Whey Protein Isolate Superfuel – The Best Protein on The Planet! Available in Two Delicious Flavors: Vanilla Bean and Cocoa Bean

- NEW: B.rad Superfruits – Organic Freeze-Dried Exotic Fruit Powder! Natural Electrolyte Hydration & Energy Powder

- Born to Walk

- The Primal Blueprint

- Primal Endurance

- Peluva.com

We appreciate all feedback, and questions for Q&A shows, emailed to podcast@bradventures.com. If you have a moment, please share an episode you like with a quick text message, or leave a review on your podcast app. Thank you!

Check out each of these companies because they are absolutely awesome or they wouldn’t occupy this revered space. Seriously, I won’t promote anything that I don’t absolutely love and use in daily life:

- Peluva: Comfortable, functional, stylish five-toe minimalist shoe to reawaken optimal foot function. Use code BRADPODCAST for 15% off!

- Mito Red Light: Photobiomodulation light panels to enhance cellular energy production, improve recovery, and optimize circadian rhythm. Use code BRAD for 5% discount!

- Wild Health: Comprehensive online health consultation with blood and DNA testing, personal coaching and precision medicine. Get things dialed in! Use discount code BRAD20 for 20% off!

- Take The (Cold) Plunge online course!

- B.rad Whey + Creatine Superfuel: Premium quality, all-natural supplement for peak performance, recovery, and longevity. New Cocoa Bean flavor!

- Online educational courses: Numerous great offerings for an immersive home-study educational experience

- NEW: B.rad Superfruits: Organic Freeze-Dried Exotic Fruit Powder! Natural Electrolyte Hydration & Energy Powder

- Primal Fitness Expert Certification: The most comprehensive online course on all aspects of traditional fitness programming and a total immersion fitness lifestyle. Save 25% on tuition with code BRAD!

- Male Optimization Formula with Organs (MOFO): Optimize testosterone naturally with 100% grassfed animal organ supplement

I have a newly organized shopping experience at BradKearns.com/Shop. Visit here and you can navigate to my B.rad Nutrition products (for direct order or Amazon order), my library of online multimedia educational courses, great discounts from my affiliate favorites, and my recommended health&fitness products on Amazon.

TRANSCRIPT:

Brad (00:00:00):

Welcome to the B.rad podcast, where we explore ways to pursue peak performance with passion throughout life without taking ourselves too seriously. I’m Brad Kearns, New York Times bestselling author, former number three world-ranked professional triathlete and Guinness World Record Masters athlete. I connect with experts in diet, fitness, and personal growth, and deliver short breather shows where you get simple, actionable tips to improve your life right away. Let’s explore beyond the hype, hacks, shortcuts, and sciencey talk to laugh, have fun and appreciate the journey. It’s time to B.rad.

Mark (00:00:38):

After the research. No running is is not the panacea to everything. In fact, it’s probably in many cases, antithetical to

Brad (00:00:49):

Mark Sisson. Another wonderful occasion of a new book coming out. I’ve heard you say in the past, I probably won’t write another book. Yeah. And then we get to talking and start realizing the story that needs to be told. So we have Born to Walk. Yeah. Why don’t we start with, um, where’d you come up with that title? I mean, what’s behind It?

Mark (00:01:08):

Well, first of all, you know, we, you and I talked about doing another book three years ago, more of an anti-aging book, you know, getting into that longevity space. And as one of the topics of it was slowing down the activity part of it, and finding ways to increase your longevity through low level aerobic activity and walking was, you know, emerging again as the sort of quintessential way to do that. The quintessential human human movement that got us down this path of like, well, do people really, you know, is walking really what everybody, you know, is cracked up to be or is running really the, you know, the main focus that people should be thinking about when they go to achieve good health, longevity, vitality, mobility, and all these things. And it turns out after the research, no running is, is not the panacea to everything.

Mark (00:01:56):

In fact, it’s probably in many cases antithetical to good health for a lot of people. So, Born to Walk was kind of a tongue in cheek response to a book that came out in 2010. I think. You know, Chris McDougal, who was a friend and did a great job writing this book, but the name of the book was Born to Run. And it sort of had this thesis that humans are born to run, that we are genetically adapted to run long distances, and that we should run long distances and that we should run long distances barefoot. And when you and I got into the research on this, it’s like, whoa, this is like, this has been miscast, this whole concept of the human prerogative, or imperative I should say, of becoming strong and lean and fit and happy and healthy. And that, and that imperative, which was requiring that you have to run, that we’re born to run, to do this, it actually doesn’t fit. And so ultimately we come down to this realization that humans are born to walk, we’re able to run, and we’re able to run occasionally as a result of walking a lot, sprinting once in a while, lifting heavy things, moving around and moving through space and time. But we’re not born to run metronomic eight-minute miles every day, day in and day out as some means to achieving some longevity goal or some health goal.

Brad (00:03:13):

Right? I mean, some of the major descriptive points are that these evolutionary biology insights are taken out of context and misappropriated. So just so no one misunderstands Yes, humans are the most amazing endurance creatures on earth, and we can outlast the antelope for four hours on the African Savannah <laugh>. What does it have to do with metronomically? Yes. Putting in miles as a modern citizen.

Mark (00:03:38):

I mean, look, everything I’ve ever done in terms of writing about human health and, and gene expression looks at evolution. And how did we evolve to where we are today with this set of genes that wants us to build muscle, wants us to burn fat, wants us to be healthy and fit and lean and not get sick. The genes are expecting certain inputs. One of the inputs the genes are not expecting is for you to run every single day. And evolutionarily, if you look back at human history, ’cause because you know, very smart people like Daniel Lieberman, who, who did a lot of research on this, and they would call, you’d call upon the, you know, the bushman or the hunters in, in Africa who would go chase an antelope for two hours. And that is the, that was the sort of concept like, okay, humans are born to go run long distances and chase animals were, we have this nuchal ligament in our neck.

Mark (00:04:33):

We have a cooling system in our sweat glands that allows us to outlast other animals in the heat. But the thing is, our ancestors did not do that every day. And they didn’t hunt a beast one day. And then that animal would last a couple of days. And then they’re like, well, what are we doing today? There’s no, we’re not, you know, we still have meat left over from the last hunt. It doesn’t, we can’t, we can’t store it. So we don’t need to go hunt another beast today. Let’s go run 10 miles for fun. Right? None of our ancestors ever did that. It was, it was literally antithetical to health to run unnecessarily when you didn’t have to. Oh,

Brad (00:05:06):

It was life or death.

Mark (00:05:06):

It was life or death. And so here we are today, thinking, well, humans, because of our genetic adaptation to being able to hunt animals over long periods of time and outlast them and wear them down, and then stick a spear in them, that does not give us the ability or, or the logic to be outright every or the right, I would say to go out every day and run again, run metronomic. So, like the hunt itself was pretty much, you know, walking, sniffing, tracking, hiding, spying, jogging, cutting the tangent, waiting over a period of two hours. It wasn’t running seven-minute miles chasing after an animal until the animal collapsed.

Brad (00:05:49):

Right? I think that’s obvious. When you see any animal that’s a prey, they can, they can dust us in the first minute and they’re gone.

Mark (00:05:56):

Yeah. Yeah.

Brad (00:05:56):

And so it’s clearly beyond that. I’ll say, so you, you’ve advanced the premise and now maybe we can go through the book Yeah. Chapter by chapter. ’cause it’s, it’s really kind of a, a two-part presentation. And the first one is to convince you if you are hardheaded and you love to run, that this running boom of the last 50 years was built upon House of Cards

Mark (00:06:17):

A house of cards. It was built upon, first of all, in no particular order. It was built upon this notion that humans are born to run. So we’re not, we’re born to be able to run. It was, and then it was sort of this perfect storm of things happening in the last 50 years where a book was written by Ken Cooper that suggested that higher you could raise your heart rate doing certain activities the longer you’d live. He has since kind of walked that back a little bit, that sort of automatically conferring longevity on anybody who raises their heart rate for long periods of time. Certainly there’s an application of that Frank Shorter winning the Gold medal in 1972 in the Olympic marathon, which, which brought attention to this long distance race that up until then the Boston Marathon had been around for a hundred years, but there really weren’t many opportunities for citizens to run long distances.

Mark (00:07:09):

And it was, there was no occasion. So as we get into the seventies, the only people who ran were people who were self-selected to be runners. Now what does that mean? It means, like me, they were too small to play football, too short to play basketball, too slow to, to play hockey or baseball. We sort of, because of our thin frame and stature, gravitated to running, not to lose weight, not to get healthy because track and field were legitimate sports. And for my own case, I was a miler and two miler I happened to run to and from school. That’s how I got about town. I, before I had a car, I literally, rather than take the bus. I ran to school. So hundreds of thousands of us, maybe millions of us self-selected to be runners. Now we weren’t running a hundred miles a week, 150 miles a week yet, because the shoes did not allow for people to do that.

Mark (00:08:04):

The shoes I started training in Chuck Taylor’s in the mid to late sixties, and then there were Onitsuka Tigers, which were these, the first real running shoes brought over from Japan by Phil Knight of Nike. And they were thin. And so you couldn’t run with bad form with these, you had to have perfect form. You had to have a midfoot strike to be able to put in any sort of training miles if you ran, if you were slogging along or jogging, or if you are overweight, or if you had Mm-Hmm. Bad form, and you were a heel striker, the shoes would prevent you from being able to penalize. They penalize you immediately. Yeah. Yeah. So you couldn’t, you so heavy people couldn’t run overweight. People couldn’t run. Jogging wasn’t even invented yet because the concept of running slow and slogging, didn’t it? It was like, again, if you were gonna be a runner, you were a runner in the sixties and seventies.

Mark (00:08:54):

So along comes Frank Shorter winning the gold medal in 72, then, you know, Bill Rogers wins the Boston Marathon in 19 76, 75, and then Jim Fixx writes a book on running and all of these things start to promote running. But the single biggest factor was Phil Knight and Bill Bowerman. So Bill Bowerman was coaching the Oregon Track Club and the Men of Oregon, these great runners, some of the best runners in the country at the time, all thin gifted runners. And they were performing very well in the world scene, but they couldn’t do the kind of miles that the coach Bowerman wanted them to do. Like they couldn’t do 80 or 90 or a hundred miles a week of training with these thin shoes because it was their feet that would tell them, that’s enough running for the week. Right. Your Achilles would feel it, your planter fascia would start to cramp up.

Mark (00:09:47):

You’d have all sorts of small muscles in the feet that would say, oh, that’s a, that’s, that’s enough running for the week. Bowerman says, let’s create a shoe that is thick and cushioned, and let’s let our runners wear these shoes and train in them so that they can do more miles. And in doing more miles, they can boost their cardiovascular, their VO two max. They could do, they can start to train at a higher rate and compete better on the world scene. So Bowerman convinces Phil Knight at Nike to make these shoes. And I had a pair, they were amazing. They were the first thick sold trainers that you could wear. And you, if you had good running form, they worked pretty well. They would, you know, prevent much of those traumas that the feet would encounter with Chuck Taylors or with the other thin running shoes.

Mark (00:10:36):

So, so now we have a situation where the track men of Oregon who are starting to run the roads and starting to run 10 Ks and, and, and marathons out of the roads, now they’re able to put in more miles. They have these thick shoes. Well, if they’re good for those guys, for the elite runners, they must be good for the joggers, the overweight and the other people. So this perfect storm of Dr. Cooper’s book on heart health and jogging being good for you, Bowerman himself wrote a book called Jogging. Jim Fixx wrote The Book of Running, and the next thing you know, running becomes this overnight sensation. And millions of people are buying these thick-soled running shoes and going out and running and, and putting in lots of miles thinking they’re gonna get healthier thinking, they’re gonna lose weight thinking they’re gonna improve their strength, thinking they’re gonna live longer as a result of that. And they didn’t,

Brad (00:11:30):

Didn’t work out well, especially for Jim Fixx one of the most prominent drivers of the running boom.

Mark (00:11:34):

Yeah, yeah. So he, you know, he famously, in fact went to see Dr. Cooper Mm-Hmm. <affirmative> and got his heart, didn’t get his heart tested. He went to, I think, interview him and said, no, I don’t need my heart test. I,

Brad (00:11:45):

I’m, I’m bulletproof.

Mark (00:11:46):

I’m bulletproof as a run.

Brad (00:11:47):

He’s ridiculed after he dropped dead of a jogging of a heart attack. Yeah. But at the time, the doctors concurred that if you ran enough miles Yeah. You were immune from

Mark (00:11:56):

Her immune from heart disease. So, you know, in the book, obviously, we talk about how absolutely wrong that is, that there’s a certain point at which some amount of cardiovascular activity, cardio activity will improve heart health. But beyond that, there may be a decrease in returns for doing that. So we have these thick=cushioned shoes that everybody is now running, and now we into the late seventies, early eighties, the shoes start getting thicker and thicker, but there is no decrease in running injuries. People still get injured running, they just get injuries further up the kinetic chain, because now what’s happening is the important information that the feet needs from sensing the ground, which is why barefoot running is still the best. Now you’ve negated this information, and now you’ve got these thick cushion shoes, and now you have overweight people thinking they’re gonna lose weight outrunning and jogging and pounding and heel striking. And all of that trauma goes up from the foot to the knees or the hips or the lower back, and people continue to get injured.

Brad (00:12:56):

So as the, as the title goes in the book, the running shoes open, the floodgates in one fell swoosh. Yeah. Because otherwise there is no running boom because it’s a ridiculously difficult sport for a human. Yeah. Even though we’re supposedly born to run, we’re not born to sit at a desk for eight hours a day and then lace up and go take off down the road.

Mark (00:13:16):

Right. So one of the things that we realized is that this running boom of the last 50 years was really wholly inappropriate for all but maybe 2% of the population.

Brad (00:13:28):

Why’d you say 2%, Mark? Because Yeah, that’s how many people break three hours Yeah. In the marathon today. And not to be politically incorrect, but you can tell us what the descriptive terms were back in the old days.

Mark (00:13:40):

So in the days of runners back when runners were runners and the field, the sport had not brought over citizen runners who were trying to lose weight or trying to get healthy through running or trying to finish the Boston Marathon because it was a notch in their belt or a bucket list item. Back in the seventies, there were just runners. And they, and so most people who ran, because they self- selected to be runners, and they had good running for ’em because the shoes hadn’t yet been invented, they ran with good running form. The times were much better across the population of runners than they are today. Today the average finisher in a marathon takes four hours and 35 minutes to finish. When I was running, and when that first part of that running boom happened, before it became weight loss and health and everything else, it was just runners.

Mark (00:14:32):

If you couldn’t break three hours in a marathon, you couldn’t even call yourself a runner. You were a jogger. And that was fine, but you weren’t a runner. A runner was somebody who could break three hours in a marathon and, you know, run a 37 minute 10 k, for instance. And there were tons of great runners in the country that you never heard about who run, who ran better in 1970 and 1980 than most of the top US runners run today. So yeah, it, it’s become this thing where everybody assumes that running is the sort of gold standard of weight loss, of, of achieving good health, of mental fortitude, and being able to overcome discomfort. And it is, for some people those things, but not for the vast majority. And that’s where this book comes in. The whole point to this book, Born to Walk, is to give everyone, not only permission to walk a lot, but to say that walking appropriately is one of the best things you can do for your overall cardiovascular health, for your musculature, for your kinetic chain as an adjunct to stuff that you do in the gym.

Mark (00:15:39):

We’ll talk about it later, but running is catabolic running tears muscle tissue down. So if you’re somebody who’s looking to build muscle and to say, I’m gonna engage in a new regimen, a new programs of I’m going to be running. I’m going to lift weights. And I’m going to be doing all these other things. Well, if you run too much is catabolic, and it tears down the muscle tissue. The best example I can give you is every great runner in the world right now, they lift weights, they go to the gym and they lift weights. But do they show any muscle? No. They’re skinny, they’re thin, they’re, they’re rails because running is catabolic and it tears that muscle tissue down. They have to do the lifting, but they’re not getting the muscle mass that we would say is now, you know, critical to longevity.

Brad (00:16:19):

So we have the shoes enabling people who shouldn’t really be running because it’s too difficult and stressful. And we’ll talk about that more with the heart rates. And then we have this other, uh, component, which is the marketing hype, and to sit back and see the amazing growth of this little sport that we participated in years ago. And now everybody knows somebody who’s, who’s run a marathon or is signing up for a marathon or a triathlon or an Ironman.

Mark (00:16:47):

Yeah. So what is it about the marathon that’s so attractive? Yeah, tell me.

Brad (00:16:52):

I mean, it’s so fascinating when we dug into this research that the whole most runners know this, that the marathon is based on this amazing legend of Greek history named Philippides. That’s why they have running stores named after him. And he was a Greek messenger who, as the legend goes, ran 26 miles from the city of Marathon to Athens to report news of victory and battle to the assembled of, uh, important people in Athens. And then he dropped dead after saying rejoice, we conquer, Nike, Nike ne Cayenne. That’s how Nike got named as part of this legend. And so the distance from Marathon to Athens is 26 miles, and therefore we all have to lace up and, and go try to do these marathons around the world.

Mark (00:17:35):

Tens of millions of people over the past, for 50

Brad (00:17:38):

Years plus 50 years,

Mark (00:17:39):

Hundred years have done this. Yeah. In sort of homage to this guy Philippides. But

Brad (00:17:45):

The story is a complete fabrication. And it was made up in a 1879 poem, this whimsical distortion of Greek history, because there was a great legendary foot messenger. They were called heterodryain the Greek army. And their job was to, you know, send messages by foot because they were faster than horseback over rough terrain. And they were, they were key guys. They were like elite performers like the, the Navy Seals. They were

Mark (00:18:11):

The, they were the 2% we’re talking about.

Brad (00:18:12):

Exactly. They were selected out of Yes. Probably one in 10,000 armed forces. You’re gonna be the runner guy. Yeah. And you’re gonna run. And so the real serendipities was an amazing heterodryain who actually ran 153 miles in 36 hours from Athens to Sparta to request their help in important battle. The guys the Spartan said, we’re on vacation, we can’t help you yet. Yeah. So he had to turn around Yeah. With a cat nap and run 153 miles back to Athens to say, Hey, we better not go to battle yet. The Spartans are on vacation. And, and Dean Carass, uh, prominent ultra marathon runner wrote a beautiful book about this with all the details. And he calls it one of the great physical feats in human history because it changed Western civilization and all that. But if we wanna honor Philippides, the marathon should be 153 or, or perhaps even 306 miles.. Yeah. Yeah. So the point of the story is all this stuff is a fabrication. Right. And a marketing gimmick. Right. And same with the Iron Man.

Mark (00:19:15):

Well, even the Marathon itself, the original, the distance from Sparta from the plains to Athens is 25 miles. And so for the, the first marathons were 25 miles, and then, and the first marathon in the Olympic Games, 25 miles. And then in 18 what year was it?

Brad (00:19:31):

The, the Queen wanted to see the, the snow,

Mark (00:19:33):

The London, the first London marathon’s, they wanted to see the, the start of at the Windsor Castle. And in order to make the the layout of the course fit, it had to be 26.2 miles. And that’s how it became 26.2 miles.

Brad (00:19:46):

That’s what my tattoo, oh, no, I didn’t get a tattoo. Sorry. Yeah. Yeah. So if you mix all this stuff into the, into the recipe, we don’t wanna discount the amazing work of Daniel Lieberman at Harvard and the life’s work of the great evolutionary biologist, you know, describing how the human evolved as persistence, hunter, hunter gatherer. We might get Professor Sisson’s slight take on that. You just hinted at it that it wasn’t really running 50 miles a week chasing beasts down. It was the brain was the key driver of evolution. But humans have all these great adaptations now we have to go into modern times and the practicality and realize that running 26 miles is a ridiculous challenge for almost everybody. Yeah. Except that 2% that can break three hours. And those are the racers. Yeah.

Mark (00:20:32):

No, I mean, and one example that, that we’ve come across just in the last year since we talked about the book, is people who say, but Mark, I love to run. And I’m like, okay, do you really love to run or do you love having run, finishing a run? And then the feeling that you get afterwards. Do you love calling yourself a runner and telling people that you’re training for a marathon, which is, you know, all well and good, but I would submit that most people don’t love to run that. It is a, it’s like saying, I love to do the cold plunge. Right? Do you love to do the cold plunge? Do you like, okay, I can’t wait to get into this, you know, freezying ice cold water? No. You love the feeling when you get out and it’s great and it lasts for a day.

Mark (00:21:10):

And so a lot of people who are into running daily, or four or five times a week, they have this idea that if they can submerse themselves in the run and overcome the discomfort of the run and put on their earbuds and listen to Metallica or whatever it is that gets ’em through the run, that that’s a good thing. I’m suggesting that there are much kinder, gentler ways to achieve great health, not get injured and support the other things that you’re doing as part of your longevity program, which would include lifting weights and stretching and all of the other protocols that we do to get fit and healthy. And that, for a lot of people running is now literally making them depressed and burned out sometimes and frustrated at their lack of progress, which we can explain why that happens. So if you really love to run, God bless you, go for it. But I’m giving people permission to walk a lot more.

Brad (00:22:07):

Well, you, you touched on probably the biggest failure and disappointment associated with the running brew, and it’s the broken promise of weight loss.

Mark (00:22:16):

Yeah.

Brad (00:22:17):

So, hey, you’re out there running six miles, you’re burning a ton of calories. Why doesn’t it work to put in miles in, in pursuit of, of reducing excess body fat?

Mark (00:22:27):

So some of this goes back to our original book, the Primal Blueprint now 15 years ago, where we started looking at how the body accesses fuel when it’s doing certain things. And we want to be good at burning fat. And people who are trying to lose weight have to understand that you’re not trying to lose weight. You’re not trying to lose muscle. You’re, you’re trying to lose fat. You’re trying to burn off stored body fat. And much of that happens as a result of how you orchestrate your diet. So you can eat carbohydrates all day, all day long, every day, and never get to the point where you’re burning off stored body fat because the body wants to burn the carbs first, and it won’t tap into the fat stores to burn off the stored body fat. Well, now if you’re that person who’s doing a lot of that, and then you say, well, I’m gonna burn off the calories because I’m gonna go run. The body, which now doesn’t really, hasn’t trained to extract energy from stored body fat, yet it’s still relying on the glucose, you know, the bloodstream or the glycogen in the muscles when you’re running even at a relatively slow pace.

Mark (00:23:30):

But for many people it’s still too high a heart rate. So now you, you go out and you, you know, you run your four and a half miles and you burn off 450 calories, most of which is glycogen stored in your muscles. And if you haven’t become adept at burning fat, yet the brain goes, whoa, we are way low on carbohydrates. We have to over, we have to eat in order to go run again tomorrow, because most runners run daily, or at least multiple times a week. And so you get into this pattern where you go to the work and you’re sweating and suffering and struggling, and you’re probably running at too high a heart rate to be burning fat anyway. So now you’re just burning off the glycogen in your muscles, and then the brain automatically overcompensates. It says, okay, we gotta, we gotta restore the glycogen by eating more carbohydrates, even more than if we took the day off.

Mark (00:24:17):

And with the idea that we’re gonna do this again in the next day. What you see over years and over decades are people lining up for the start of a 10 k or a Turkey Trot or a marathon who are still 15, 20 pounds overweight, sometimes more than that, who have been relentlessly training and beating their bodies up and incurring the injuries. And yet they haven’t trained the body to burn fat because they were training at the wrong heart rate, a heart rate, which would’ve been better suited to burn fat if they had walked and not run.

Brad (00:24:51):

And then there’s also that other layer of the distinction between subcutaneous fat, which is unpleasant. And I’m not happy about my appearance of my thighs or my rear end. And then the truly health, destructive, visceral fat. So we’re talking about two different kinds of fat and how that weighs into the broken promise of running.

Mark (00:25:11):

So, you know, one of the things that happens if you are struggling with your running, and if you’re running inappropriately because you’re overweight, you’re a heel striker, you’re incurring injuries, you’re trying to, you know, some people put on a rubber suit ’cause they wanna sweat, and you’re running at too high a heart rate to be legitimately training to improve. And what happens as a result of all of this is that the body thinks that you are in a, in a life or death situation and secretes the brain starts to tell the adrenals to secrete cortisol. Cortisol is a sort of a life or death emergency hormone. It’s an anti-inflammatory in, in small amounts, but it’s a, it’s very inflammatory in large amounts and chronically. And so when you secrete cortisol, one of the things that happens is your body, it tries to create more glucose to do the work you’re doing right away.

Mark (00:25:59):

And it prevents the, not only prevents the burning of fat, but can promote the storage of fat. And not just subcutaneously, but around the organs, what Brad is referring to as visceral fat, which is the fat that really, if you, if you hear people talk about, you know, an apple body being the most at risk for heart disease and diabetes. That’s the apple body is that visceral fat, that that’s fat that’s stored around the center part of the organs and around, you know, around the liver and around the rest of the organs and mesentery and things like that, not distributed evenly on the outside of the body. So you have to be very careful that even if it looks like you are shrinking a little bit from the running you’re doing, but you’re running inappropriate at a too fast a pace, you’re working too hard in your workouts, it may be that you’re literally, you’re shrinking because you’re tearing up muscle tissue and you’re depositing this fat around your organs.

Brad (00:26:53):

So I guess the, the simplified takeaway is if you’re trying to reduce excess body fat in a stressful manner, in an overly stressful manner, you are gonna be predisposed to even adding visceral fat. And you get this skinny fat physique, which is the essence of even a pretty accomplished runner where they’re keeping, you know, extra pounds off, but they’re not at all healthy.

Mark (00:27:20):

Right, Exactly.

Brad (00:27:21):

And so that’s a big broken promise ’cause it’s probably the number one goal of people out there Yeah. Puffing and puffing Yeah. And putting in miles. Then we get to another broken promise, the broken promise of cushioned shoes. Yeah. And I think we’re specifically highlighting the ridiculous advertising message that these shoes are gonna help you avoid injury and control pronation and all these things that no research has ever shown to be true. And then furthermore, you touched a little bit on how they’re destructive to your health, but maybe we can get a little deeper since you’ve been sort of interested in shoes lately. Yeah, as I understand,

Mark (00:27:55):

Well, first of all, the, it’s, it’s really, you know, it’s laughable. The advertising in the eighties and nineties and the, and early two thousands even now, where they talk about the tech, the tech in the shoes. Mm-Hmm. <affirmative> like the, the, these have, you know, fore foot motion control, midfoot stabilization, rear foot stabilizers. They’re gonna control for pronation. They’re gonna do all these things that the buyer is supposed to believe is going to decrease the risk for injury and allow them to run pain-free and injury-free. You know, more often. And the result, or the actual truth is that these shoes have done nothing to decrease running injuries. And you could argue that they’ve even potentially increased running injuries. Mm-Hmm. <affirmative>. But it’s not, it’s not that these issues cause injuries, it’s that what they do is they forgive bad form <laugh>. Right. They allow people to run with bad form thinking at every footfall that they’re running on a cushion, on a cloud, on a, on a pillow.

Mark (00:28:58):

But what’s happening, as we said a little bit earlier, we touched on earlier, the feet need to sense the ground underneath in order to inform the brain exactly how to organize the kinetic chain Mm-Hmm. To absorb the impact of that footfall. So while I’m running barefoot, I am very cognizant, like when I step on a gravelly surface, I’m landing midfoot. I’m not landing on a heel strike, I’m landing on midfoot. By the time I weight that front foot, my brain has all the information it needs to know about the temperature, the tilt, the texture of that ground, and how to scrunch the toes, how to, how to maybe bend the arch, how, maybe roll the ankle out maybe a little bit. How to, how to bend the knee, which is supposed to only bend in one plane, how to roll the hip, all of which is part of this kinetic chain that we depend on for a perfect gait.

Mark (00:29:48):

And by the way, everybody, whether you’re knock knee, duck footed, pigeon toed, wide hip, narrow hip, everybody has a perfect kinetic chain for themselves. Provided the brain is able to organize that particular kinetic chain in a way that best absorbs the shock. Now you put a thick, restrictive encased shoe over a foot. Mm-Hmm. <affirmative>, you, you negate all of that sensory input. Mm-Hmm. <affirmative>. So now the brain has no idea of, of the temperature or the texture or the tilt of the ground. And so it has to sort of guess. And a lot of times people will then maybe roll an ankle or they get bad knees because the knees start to bend sideways, whatever it is, because of this loss of information, you know, the, the kinetic chain is compromised. And yet because it feels soft and cushiony at the time to the runner, they’re like, oh, must be okay, because I don’t feel any pounding. Right. The buck stops at the hip. So, so much of this, the pounding is, you know, not just, it’s, it’s deviated a little bit from the feet, but it’s then it’s, it’s then driven all the way up to the hip. So you can quote lieberman’s testing on that, but, but basically the amount of shock absorbed by the hip versus in a shad runner versus a a barefoot runner is Yeah. Twice.

Brad (00:31:12):

It’s, it’s mind blowing. And I, I don’t think, I don’t know why is a prominent researcher from Harvard University putting this information out there, but it goes over our head possibly due to the billions of dollars of marketing, the shoe technology, the research from Dr. Lieberman at Harvard shows that when you’re wearing a cushioned shoe, you absorb seven times more impact trauma than when you land on a hard surface in bare feet. Right.

Mark (00:31:39):

But absorb means you transfer it to the hip, you don’t absorb it. The the shoe doesn’t absorb it, it,

Brad (00:31:46):

It imparts more. Yeah. Yeah.

Mark (00:31:48):

It, it transfers seven times more impact trauma. Yeah. So

Brad (00:31:51):

How, how is that possible? Yeah. And we have, we have another chapter about the magnificent human foot and how it can absorb impact. Yeah. But I remember the quick visual from our primal con retreats when barefoot Ted would have order everyone to remove their shoes, get onto a paved sidewalk and run barefoot for 50 meters down the sidewalk. Yep. And immediately you saw a pack of average people perfect form running with perfect form balancing like a deer gracefully down the sidewalk Yeah. Than what happens when they put on their cushion running shoes to go for a five miler. Yeah. That was the point you were making before, is that the shoes enable poor form. Why do people have poor form? We can, we can talk about a lot of reasons. One of ’em is ’cause they’re sitting like we are Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. And a lifetime of sedentary patterns.

Mark (00:32:38):

Well, and a they have poor performed because they have a lifetime of being a heel striker and running literally running too slow for the most part. You know, and, and people who are

Brad (00:32:46):

Not, no offense, but yeah. No offense. No, you can’t get a midfoot strike if you’re really plotting and shuffling. Yeah, yeah. That’s not running. Correct. That’s, uh, injurious, jarring, breaking heel striking technique as we call it. Yeah. And so I guess that’s the main attribute that you’re trying to avoid is this overstriding shuffling pattern. Yeah. And I think, um, the reason it comes up is poor overall fitness adaptability. Yeah. Where you have, uh, weak, dysfunctional glutes, you have tight hamstrings, you have tight hip flexors from sitting. And so the sport of running is super difficult and challenging to more run more than a few minutes. And that, I mean, back to that chapter one point is like in the old days, no one could do it except really fit people. Right. That worked really hard. Right. Now you can put the shoes on. And again, I want to get further into, if it feels good in my super cushioned shoes, what the heck’s wrong with that? These shoes are the most comfortable I’ve ever worn. But what happens to the Yeah,

Mark (00:33:44):

Yeah, yeah. The

Brad (00:33:45):

Impact That’s seven times impact load.

Mark (00:33:47):

Yeah. No, it, over time, it, uh, you know, it, it causes lower back issues. It causes, you know, potential hip, hip replacement issues over time. I mean, it’s just Right.

Brad (00:33:58):

I mean the other research is that the, the beautiful cushion soul absorbs 10% of the impact trauma. Yeah. Now that’s really great for those Oregon runners you talked about that are running a hundred miles a week and six minute miles

Mark (00:34:08):

with perfect form.

Brad (00:34:09):

Right. They get a little, they get a little loose

Mark (00:34:11):

With those guys get hip. Yeah. Yeah. If, if they run, if you run with perfect form, then you know, the shoes are, are a boon to running and they allow you to put in more miles. Now, <laugh>, what is, is putting in more miles necessarily a good thing if you’re not a world class elite runner. I mean, you know, you and I know lots of relatively good age group athletes who have had other issues, cardiovascular issues from having run too much. Right. Uh, because they were able to run too much because of the groovy shoe.

Brad (00:34:43):

Yeah. That’s heavy. Yeah. Yeah.

Mark (00:34:45):

I mean, I, you know, I, part of my story is I have heart issues today. I overtaxed my heart because I was able to put in the extra miles, even though I had good running form, I was able to put in the extra miles, which then just, it just went in the bypass, the kinetic chain up to the, to the cardiovascular chain. And, you know, I have issues as a result of that. We, and we talk about that in the book about how even some of the best runners in the world have had heart problems, you know, had died of heart attacks, or had heart attacks and, and lived and had pacemakers installed, they had defibrillations all this. So, you know, running, running isn’t the, again, the panacea. It’s not the be all. It’s not the, it’s not the gold standard for fitness and health that many people make it out to be.

Brad (00:35:35):

Maybe we should make a new, a new sport where you can only train and race barefoot and have those limiting factors in. But as we trash running shoes, rightfully so. Yeah. And shame on them for the, the misleading advertising, not just for me, but from the British Journal of Sports Medicine saying, with a comprehensive study of years and years of running shoe marketing and fake research that no study has ever proven that running vision has reduced impact trauma. And that the, it mis the advertising is misleading, re resulting in a public health hazard that’s big, right. From, from a prominent journal. Right. Now I wanna say in fairness, like the running boom got people, let’s say, off their butts and how exercising, so that’s a good thing. Mm-Hmm. <affirmative> the running shoes that have been made for that Mm-Hmm. <affirmative> enable people that otherwise couldn’t do it.

Brad (00:36:21):

So we’re just saying, look, if you’re gonna do a specialized activity, like I love high jumping, I don’t high jump in bare feet ’cause I’ll torch my achilles tendon. So I wear a steel plated spike with spikes on the heel Right. For specialized activities. So the running shoes are just fine for that, but then we have to also add that component of good form. Right. So it’s use your shoes if you want to go run, and then we’re gonna talk about heart rate shortly. But the, the main point is that the human is very well adapted to run with good form. Yeah. Yep. So then we get into chronic cardio, which you, you hinted at, and this is kind of the worst kept secret, I think in the endurance scene.

Mark (00:37:01):

The first blog post I ever wrote, 2005 actually, I wrote for my mentor Art Devaney on his site. And it really described my experience as having been an endurance athlete and having been caught up in this notion that more is better and that longer and harder and faster was better to the point that it wore me down and, and, and forced me to retire from competition, compromised my health. Because, at the end of the day, if you’re looking for good health, it’s very possible that you can overdo the cardiovascular part of your training. So yes, people have to do cardiovascular training. We’re gonna talk about exactly what that looks like. But so many people go all in on cardio and they’re like, oh. And this goes back to not just the days of running, but the days of aerobics classes. Right. Where, where there’d be aerobics, teachers who would teach four classes in a row, they’d be doing four hours worth of high level, high intensity, high-end aerobic stuff. Yeah. And, uh, there is a point at which the cardio becomes what we call chronic. It becomes not a health giver, but a health taker. And it, and it, and it may not be some, you know, life-threatening thing as much as it might be just you burn out and you, and you,

Brad (00:38:18):

Uh,

Mark (00:38:19):

It, you it

Brad (00:38:19):

Visceral fat visually

Mark (00:38:20):

Accumulation of, of this visceral fat, again, because of the chronic stress hormone production. As a result of you trying to go out there and override the brain’s general tendency to be, look, let, let’s keep it, let’s, you know, let’s keep it in check and let’s your limbic system, you know, your, your reptilian brain says, whoa, whoa, whoa, stop. We can’t do this. But the, you know, the cognitive party says, I can over, I can overcome that. Yeah. I can do this every single day. I can, I can, and I will. And I’ll like our ancestors, in addition to not wanting to train hard every day because it was antithetical to their health couldn’t because they couldn’t, they didn’t have access to, um, cereals and breads and pastas and rice and gels and of coke and all of the sugary things that, that enable runners to, to finish their workout today and immediately restock Mm-Hmm. <affirmative>

Mark (00:39:13):

With 600 grams of carbohydrates so that they can do it again tomorrow. So that’s another aspect of the running boom that, that compromised my health and millions of others, was this idea that because we have access to plentiful carbohydrates and because carbohydrate management was sort of the be all and the end all of training at, at a high level, we could just carbo load every single day. Well, carbohydrates tend to be in inflammatory as well. So now, yes, you’re replenishing your glycogen, but now you, you’re causing sort of a systemic inflammation throughout the body, which is being exacerbated by the amount of training you’re doing, which then maybe impacts your arthritis or your, you know, irritable bowel syndrome or whatever it is you’re dealing with. We, we coined the phrase chronic cardio to describe this situation where you’ve taken a good thing too far. Mm-Hmm. <affirmative>.

Brad (00:40:09):

And it seems to be, speaking of marketing hype, we are programmed and conditioned to consider a workout to be something that really pushes and challenges us and makes us sweat. And we wanna feel exhausted and depleted at the end. Yes. Otherwise, what are we doing twiddling our thumbs? Correct. And even today, with the zone two cardio, who ever made these zones up? I don’t know, but like now we, we zone everything. Yeah. And there’s great promotion of zone two, which is a comfortably paced exercise. Yeah. But no one ever mentioned zone one. Yeah. And how incredibly valuable Right. And, and useful it is to, to exercise at a level that’s super comfortable. But then back to the Primal Blueprint and, you know, the aligning of our fitness program with ancestral health, we don’t just want to blast our hearts and use all our energy up. And that’s another drawback is you don’t have the energy to do the lift heavy things is the sprint once in a while and play,

Mark (00:41:03):

Or, or by the way, live your life, right?

Brad (00:41:05):

Yeah.

Mark (00:41:05):

No, you want to have the energy to

Brad (00:41:07):

You go home from parties at 8:30 ’cause you gotta run 20 the next day. Yes.

Mark (00:41:10):

Yes. And, that became sort of the, you know, the standard operating procedure for most endurance athletes was, I have to do this every single day. Well, why are you doing it every single day? If you’re a competitive athlete, you have to do it every single day, you take a day off. But if you’re not a competitive athlete, why are you doing this? Like, if you think I’m gonna train my ass off to run 03:42 in a marathon, I’m gonna say, why, why would you do that to yourself? Like, you’re not a good runner. I’m sorry if you’re Yeah. If you, you know, you’re, but you’ve done it. If you’ve done a 03:42 and you’ve done it once and you know, great to go, go do it again. But why are you doing that? Because it’s not competitive. You’re not even gonna win an age group, and yet you’re tearing your body apart. You’re doing things that are, again, antithetical to health and longevity and happiness and spending time with your family. So part of, part of what we’re doing with Born to Walk is we’re looking at a holistic picture. Like, how do I, how do I, how am I able to still call myself a runner? Here’s a, here’s a thought experiment for you. Okay. You’re somebody who, you’re a 03:42 marathoner. Okay? I don’t wanna pick on you guys, but, and you say, I’m a runner, I’m a marathoner. Great. You’re a runner.

Brad (00:42:28):

You’re in the top 10%, by the way. So Mark’s picking on and off. Yeah. Yeah. Don’t, don’t feel too offended.

Mark (00:42:33):

Right. But that’s, you know, that’s basically 7, 8, 8 and a half minute miles from me. Very impressive. Okay. So it’s, it’s, it’s a, it’s a feat. It’s a feat. But at what point are you, are you trying to improve you, you’re, you know, your speed. Are you trying to, are you doing this to rack up multiple finishes over the course of a year? Because it’s not going, you’re not gonna improve unless you reorient your training to become better at burning fat. Right. And it may be,.May be that you don’t improve from a 03:42. So at which point you, I, again, I would say, why are you doing this? Like, like it’s, it’s not in conferring longevity. What is the reason that you’re choosing to do this? As opposed to hiking at an easy heart rate, lifting weights in the gym, stretching, feeling good, getting back to your family life and just, you know, and, and living your life in its totality. Yeah.

Brad (00:43:34):

And, and we both know people that will come back with a spicy quip right now saying, I absolutely love it. It’s my social experience. It’s everything. Yeah. And to them, I think the important message is do it fricking right? Yeah. Because 03:42 isn’t that fast for someone who dedicates this many hours a week and watches their diet and has a trainer to come stretch them or, or whatever. They’re, they’re all in for this thing. Yeah. You can do a lot better by taking better care of your body and then we wouldn’t have to address this. Right. Elephant

Mark (00:44:04):

In the who. So, and that was my point. So, so my point, which I lost in that last, is if you call yourself a runner because you’re doing the training and you’re putting in 40, 50, 60 miles a week, what if I, if I said I could have you running eight and a half minute miles for 10 miles, I could have you running seven and a half minute miles for 10 miles once a week if you walked more, lifted weights and did all this. So now you’re only running once a week, which you’re a faster runner. Mm-Hmm. <affirmative>. And you can still call yourself a runner. Mm-Hmm. <affirmative>, it isn’t like you need some x amount of mileage on your log book to say, contrary to say, I’m a runner. Right. If you can, you know, if you can run faster on fewer miles and a little bit more walking and, and this is what we’re trying to say in the book and train, train yourself to do that. Yes. You could still call yourself a runner, you know, so you haven’t, you haven’t lost your moniker of being a runner, but now you’re more well-adapted, well-rounded, you’re not getting injured as often. You’re not as burned out from a long training sessions, you know, those long Sunday runs or Saturday runs.

Brad (00:45:09):

Well, you did this yourself Yeah. When you were 38 years old and retired from elite competition. Yeah. Maybe you should tell us about that lifestyle transition and then what you did for fun on the weekends, beating up on the poor head down endurance. Yeah. Say sport athlete

Mark (00:45:23):

Right. So I was a, I had a 10-year period as an elite athlete and, and was a decent marathoner and halfway decent triathlete. But then I saw the folly in my ways. It was, it was way too much training and not enough reward for it. So I retired, but I started coaching peo,ple and I started doing not just elite athletes, but I started coaching average citizens on how to lose weight. So I was spending a lot of time, I was spending three hours a day walking with my clients, just walking, or I was in the gym and I was lifting weights with my clients, but not lifting heavy. I was just lifting weights. And then once or twice a week on my own time, I’d go to the track and I’d do a pretty intense track workout. I may run repeat miles or something like that, but my, I had one workout a week from where I would do that.

Mark (00:46:10):

And then I did that for a few years, and then I started coaching this professional triathlon team, and I was now 38 years old, and I’ve got all these top triathletes and they wanna go, let’s go by 80 miles today and then we’ll run 10. Right. And I could, I could ride with those guys. These are guys who are the best in the world at what they do. You were one of ’em, you were ranked third in the world in triathlon, and I could hang with you for one workout once a week or twice a week. I couldn’t do it every day like you were doing, but once or twice a week I could hang on the workout and do that. So what I learned from that was I could stay fit at 38 as fit as I was maybe at 28, on much less training time as long as I trained smart and did very low level activity in between those hard sessions.

Mark (00:46:57):

And so then I would get into a race like the Desert Princess and, you know, and, and finish 11th, you know, not just 11th overall. One year in the Desert Princess, one of the ones that you might have, you might have won. So, um, where am I goal with this? It’s just that you don’t need to train metronomic hard running every single day, not improving and feeling discouraged about the lack of progress when there are ways that we can incorporate lower heart rates, which sometimes require that you walk to achieve that fat-burning zone, that that zone one or two level. So when you run a, I don’t know, a 04:45 marathon, I don’t even know what that is in terms of minutes per mile. It’s like seven or so, 8, 9, 10, 11, 11 minute miles. You know, most people can walk 13 and a half minute miles. Mm-Hmm. <affirmative>. So you’re not even that, you’re

Brad (00:47:54):

Just pounding.

Mark (00:47:54):

You’re just pounding instead of walking. Yeah. And, and getting a nice, you know, grippy feel from your feet. And, and, and now you’re, you’re going from catabolic to anabolic. So there, there’s, we talk about it in the book. There, there are a lot of ways in which you can get better at what you’re doing, aerobically by slowing it down and abandoning this notion that I have to run no matter how slow I’m going, I have to run. No, if you’re going that slow, you should start walking and you should burn fat, and then you should earn the right to run a little bit faster. Mm-Hmm.

Brad (00:48:31):

<affirmative>. So we’re, we’re into this Part One of the book, and we’re almost to part two. And as you might’ve guessed, part one, sort of the, the, the, the broken promises and unintended consequences, there’s one more chapter, which I think is, is the heaviest. And it was really, you know, sobering to, to dig into the research from the behavior experts, the psychologists, um, the title is The Ordeal of the Obligate Runner. Yeah. And the obligate runner was tdefined back in early 1970s. And it, what’s sobering is like this shit still happens today where people get sucked into this vortex and talk about like the, the personality aspects of getting into this chronic cardio.

Mark (00:49:09):

Yeah. It’s, it is as much an addition as, you know, cocaine or sugar or, or heroin in some cases that people, uh, you know, I think we, we cite several examples of people who’ve run every single day for 30, 40, 45 years without fail through appendicitis and broken legs and all sorts of things just because they have to run. So there are a lot of people who feel that it’s, it is their obligation to do something that is difficult to, you know, it’s almost like a David Goggins, if you know who that is. Kind of, kind of mentality. Like, like, I gotta be hard and I gotta be tough and I gotta do it every single day and every single day it means every single day. And I’m a piece of shit if I take a day off. And it becomes this, um, such a mindset that if you do take time off now, you now the guilt gets laid on.

Mark (00:50:05):

You feel horrible about taking time off. I shouldn’t have taken a day off. It’s like the people who, you know, you, you’re running in a, you see this happen in a marathon where people are running and they, and it just, you know, it’s not their day and they get to 18 or 19 miles and they’re like, I, I just gotta, I, I can’t keep going. I gotta drop. I drop and like three minutes later, like, oh, shit, I could’ve, you know, now I feel good again, I can’t put on again. Right. So, yeah. Anyway, um, more on the obligate runner. Yeah.

Brad (00:50:32):

I think, you know, the definition of addiction is where you need to get your hit to get back up to baseline. It’s not bringing joy and fulfillment into your life. And I think there’s the extreme examples where people really, you know, spiral out and they’re, and they’re, you know, over training to the point of a stress fracture, which I think is the ultimate example of an addictive approach to running because you get warning sign, warning sign, further pain, further pain, further away, run, run through it. Finally, your bone cracks from all the pressure you put on it. But on that moderate level, yeah. There are so many millions of people in this category where due to the confines and restrictions of modern life, they really feel that intense need to get out and bust out and burn some energy. And again, that’s a wonderful balance.

Brad (00:51:19):

And even pursuing these competitive goals is wonderful. Sir Roger Banister, the first four-minute miler, he said, struggle gives meaning and riches to life. Yeah. But it’s the distortion of the struggle, turning it into something stupid. Health destructive, not promoting of longevity. Yeah. Not even promoting of mental health. Yeah. That’s where we’re pointing this distinction, saying, Hey, put on the brakes for a second and ask yourself, where’s this fit into my life? And hopefully it’s at a wholesome, wonderful place. Like our many friends that are devoted runners, Tom Hodge and Dr. Stevie Kobrine. He just did the Colorado Trail, spent his summer going 468 miles on 28 segments with great pictures and wonderful. Yeah. That’s a lot different than someone who’s agitated with their significant other at the race finish, because they were four minutes slower than they’d hoped. And that’s the part that we’re exposing and saying, Hey, enough already.

Mark (00:52:10):

Yeah. One of the things about the obligate runner is this chasing the high. Right. This chasing the, the endorphin rush, what they call, they call it the runner’s high for a very long time. It’s interesting because when we look at the, uh, the nature of endorphin production, it’s sort of a, it’s sort of a life or death hormone. It’s a fight or flight hormone. It’s, it’s the kind of thing that, like if a zebra is being chased down and eaten alive by a lion, it’s the endorphins that allow the, you know, the zebra to finally kind of give up and not fight anymore. Mm-Hmm. <affirmative> and just feel that euphoria in the face of death. Right. So endorphins are this morphine-like substance that we create by creating a life or death, like a, like a situation running hard every single day.

Mark (00:53:01):

Yeah. And we build up these endorphins, which we sort of, we interpret as the runner’s high, but if you look at their function evolutionarily, it’s the same thing that would say and endorphin would be endorphin the humans who have haven’t eaten for three days and have out and gone out on a long run and failed to catch the beast. Mm-Hmm. <affirmative>. And now they’re, they haven’t eaten for three days. They failed to catch the beast. They’re, they’re tired from having done endorphins. Endorphins are what keep them from just giving up and saying, I I I’m gonna die right here. No, it’s sort of a feel good, um,

Brad (00:53:38):

Ketones and endorphins that carry on.

Mark (00:53:40):

Yes. It’s sort, it’s sort of a feel good neurotransmitter that allows them to maintain optimism in the face of a very bad situation. Yeah. So now we find ourselves trying to recreate this on a daily basis, and the obligate runner tends to seek this endorphine rush on a basis, maybe because there’s some shit going on is, or her life maybe, maybe they don’t wanna, you know, face the fact, I mean, one of the things that I got as a, when I was training for elite competition was, oh my God, Mark, you’re so dedicated. Like you’re so disciplined to go out there every day. And I’m like, I don’t tell anybody. It’s not disciplined to go out and train. It’s disciplined to take a day off, go to work, put in a full day’s work, you know, come back to training a day later as recharged and regenerated, but the discipline is doing things that you don’t want to do when you’re a runner.

Mark (00:54:36):

You convince yourself you wanna do these things and then it’s no longer discipline. Yeah. My career ended, I can tell you exactly when it ended. It ended at the end of a five-day week where I ran five consecutive 20 mile runs. So, so Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, 20 mile run, 20 mile run, 20 mile run. And each day was faster than the previous day, and each day I was feeling better and better. I was in that, I was in that feel good euphoric zone until I injured myself. I got a, a hip tendonitis issue that literally took 30 years to resolve. But, it was because I was so in that endorphin zone, in that rush zone, not paying attention to the signals that were being passed. And when I say I ran faster every day, I was, you know, they were like at sub six thirties, the first, the first day and six fifteens and sub and, you know, it was around, you know, it was sub sixes by the fifth day, and I was feeling great. That’s a hundred miles in five days of sub six minute miles. I mean, a lot of, you know, a lot of the north African runners now would say, ah, you know, ed laughing normal. But, um, you know, for me that was really pushing the envelope. Yeah. And it cost me, but it cost me, because I was so invested in the obligation, the obligate of getting out there and completing the workout.

Brad (00:55:59):

I mean, the original researchers that coined the term drew a corollary to anorexics and devoted runners Yeah. To the point where they pursue their quest to the extreme detriment of their health. Yeah. Just to close that point, I mean, it’s pretty heavy because deep down a lot of this endurance community would benefit from looking in the mirror and saying, what am I doing here? Yeah. And as we, as we proposed, a lot of people are running away from stuff in their life. Yeah. Which, you know, there’s different ways to cope. This is better than going down to the corner saloon. And unfortunately, the problem is kind of swept aside, and to the extent that they use running for extreme addicts to, to get off other substances because it gives them Yeah, yeah. Dopamine spike. So the runner is trying to do the right thing. Yeah. You don’t, you don’t get a lot of support or empathy and that, that part Yeah. Needs to be brought to the forefront.

Brad (00:56:54):

And that gets us to part two mm-Hmm. <affirmative>, when we talk about the warm, fuzzy, wonderful benefits of doing things. Right? Yeah. Starting out with slowing down and building an aerobic base. And you’ve hinted at this. So now we’re going to really define this term Fat Max, and the difference between being a sugar burner and Right. A fat burner.

Mark (00:57:14):

So we touched upon it earlier, but most people are pretty good at burning sugar. And because they consume a lot of it, they, it’s, you take it, sugar, glucose comes in the form of carbohydrate, which is again, breads, cereals, pastas, rice, sweetened beverages, desserts, ice cakes, candies, cookies. So all of these things, they’re very high in sugar, whether it’s, you know, having waffles and toast for breakfast, or pancakes and cereal for breakfast, and a sandwich for lunch and some chips and pasta for dinner and bread rolls. And over the course of a day, many people consume 3, 4, 500 grams of carbohydrates. And as in so doing, um, the body says, we got this sugar coming in, this glucose, it’s toxic above a level of five milligram, one teaspoon per the entire blood system in your body. We have to get rid of it, we have to burn it off.

Mark (00:58:07):

So the body preferentially burns off glucose first, and it never really gets a chance to take fat outta storage. Meanwhile, excess glucose converts to fat. So now you’ve got this double whammy where you’re con consuming a lot of glucose, a lot of carbohydrate. You get, you store the excess as fat, then you run out of glucose in the bloodstream. So the brain says, we gotta go eat more carbohydrate. But you can’t take the fat outta storage because you haven’t trained the body to, you haven’t built a metabolic machinery to be able to take the fat out of storage and burn that as fuel and then bypass that whole thing about getting hungry and getting hangry and you know, hunger, appetite and cravings. So the problem as an athlete is if you don’t pay attention to the fuel source, you will continually burn this glycogen, this stored glucose, and you won’t, you still won’t access body fat.

Mark (00:58:57):

Yeah, you will a little bit. But we see athletes who, over the years, who aren’t really paying attention to this and aren’t training appropriately, gain a pound every year, two pounds, three pounds every year, and over a couple of decades they put on 30 or 40 pounds and they’re like, wait a minute. I’m at the gym every day. I’m running on the treadmill. I’m struggling and suffering. I’m sweating. How am I not losing weight? Well, that’s why you haven’t trained your body to become good at burning fat. How do you do that? Well, number one, cut carbs outta your diet. Not completely, but lower the carbs in your diet. And then most importantly, for your workouts, make sure that you are performing at a level, a heart rate at which your body says, we don’t need this fast burning, quick burning fuel from glycogen. We can rely on the stored body fat to fuel this low level activity.

Mark (00:59:45):

And we’ll save the glycogen, we’ll save the carbohydrate, we’ll save the glucose for when we ramp up the heart rate to 170, 180 190, or even 140, 150, 160. So the idea behind this maximum aerobic function, this, this special heart rate that we’ve, that research has shown the past several decades to be sort of very, very consistent within a certain range. It’s typically 180 minus your age is the maximum heart rate at which you should be training. And below which anything else you’re, you’re doing, you’re burning fat above which you start to burn carbohydrates, glycogen at a much higher rate.

Brad (01:00:25):

Right. I mean, a simplified discussion, you’re always burning a little bit of this and a little bit of that, but that Fat Max heart rate is key because that represents, and this is found in the laboratory. Yeah. The maximum number of fat calories you’re burning per minute. Yeah. And so if you were to speed up, you’re burning more total calories,. total calories. And When we obsess about how many calories we burned on our, on our exercise machine, we don’t get it. That we have all these compensations that kick in when we push ourselves too hard. Right. So that Fat Max is so important when you train at or below that, you’re now building these fat burning capabilities. And guess what, when it is time to go faster, such as in a race environment or, or whenever you wanna do that once a week thing. Mm-Hmm. <affirmative>, now you’re so good at burning fat that you spare glycogen right

Mark (01:01:10):

Now. Now instead of, let’s just say you’re running eight miles for your big run of the week, and now instead of getting, you know, 80% of your calories from carbohydrate and 20% from fat, now you’ve trained yourself to get maybe 40% of your calories from carbohydrate and 60% from fat. So you, you continually work on this building, this aerobic capacity and this ability to burn fat more efficiently, which manifests itself in an increase in the number of mitochondria where fat is burned in the cells and increase in the efficiency of those mitochondria. So now you have like increased efficiency and double the mitochondria, now you’re burning much more fat and where’s that fat coming from? It’s coming from all the areas you want to get rid of the fat. That’s, I would suggest what most people want in their training program. I don’t think, like if somebody said, okay, you know, I’m gonna bust my ass and train my ass off to go from 03:42 as a PR in a marathon to 03:35, or I’m going to be much more consistent and I’m gonna drop from 30% body fat to 14% body fat through the appropriate training, regardless of what my time is, I think people would probably say, well, the hell with the, with dropping 12 minutes off my time, I’d rather drop 15% off my body fat.

Brad (01:02:36):

Oh my gosh. They have research showing that if you just have a lighter shoe, you save four minutes over a marathon and so forth. Yeah. I think the magic here is that you’re allowed to build without this constant struggle and exhaustion and depletion and extreme appetite when you just slow down. Yeah. And we mentioned Elliot kgi a lot in this chapter because he has presented his training log for all those to examine, and the exercise physiologists and the coaches have looked at the greatest marathon runner of all time, one of the greatest human endurance athletes of all time, 01:59 for the marathon. And it was found out that he runs 82 to 84% of his weekly mileage in what we would call zone one. Yeah. Which is ridiculously easy, vastly slower than his pace per mile for the marathon. And yet the average runner literally is training their body harder and more stressfully than the most gifted and greatest runner that we’ve ever seen on the planet. Yeah.

Mark (01:03:35):

People are training in zone three and zone four, what we called in the book we wrote eight years ago called Primal Endurance, that, you know, we called it the black hole of training, the No Man’s Land where you’re not running slow enough to burn fat, you’re not running fast enough to train the glycolytic system, you’re just beating yourself up. Mm-Hmm. And that’s the, I think one of the take home messages is so many people train consistently in zone three, four and five, three and four, which again, isn’t improving any part of their ability to race faster. And all it’s doing is beating them up on a regular basis. Yeah. You’re

Brad (01:04:10):

You’re putting like high octane fuel into this beat up old Toyota Camry and racing at the, at the streetlight rather than, you know, taking the time to build a Ferrari engine Yeah. And then go and, and perform at a higher level. And I think when you talk about that ratio of who’s burning fat and who’s burning sugar, that essentially is what you’re seeing on the street in a major marathon. Yeah. Where the winners, who The winners, the one who burns fat the best, most efficiently. Yeah. And Kipchoge’s running 04:32 per mile for 26 miles. Most runners could not hold that pace for more than 10 seconds or so. And they have that funny treadmill. Yeah. You can see this on YouTube where they set the treadmill at world record, marathon pace, and then you jump on and a lot of people are spit out the back into the pads because they’re immediately glycolytic. They don’t have the mitochondrial engine, they don’t have the big engine Yeah. To be able to carry on at a fat burning pace. Yeah. And so, relatively speaking, most runners should be doing. Now here comes the punchline. Most runners should be doing 82 to 84% of their training in that comfortable fat-burning heart rate. Which is

Mark (01:05:16):

What kind of pace walking.

Brad (01:05:19):

Yeah. Yeah. The human gait switches from walking to needing to jog at around 14 minutes per mile. Yeah. So this is super simple. And one of the graphs is, when do I get permission to run in the book? And the permission is when you hold Yeah. Your Fat Max pace, what speed do you proceed at? Yeah. And my running friends that have been running for years, since we raced in high school and we’re years and years later, they’re running down the street. Their heart rate’s at 120. Steven Dietch is running eight minute miles that this 60-year-old. Fantastic. Yeah. Yeah. What happens when that person comes home, they feel refreshed, energized, light on their feet. They’re not slogging around because they did what amounts to a walk from the vast majority of today’s serious runners. Yeah. Forget about recreational people that are just getting started.

Mark (01:06:06):

Yeah. Agreed.

Brad (01:06:07):

That’s as simple as you can take it, monitor that heart rate, check your pace, and, oh, excuse me. You can pace yourself for a mile and see what your pace is. But if you’re planning to go for a five miler, you’re gonna wanna stay in Fat Max the whole time, which means your average pace per mile is gonna be way slower. ’cause the longer you run, the slower you have to go, because of course you get tired, your heart rate goes up. So a lot of people are trying to hold their pace on a run rather than hold their heart really at the correct zone. Yeah. Rethinking everything and being kinder, gentler. So that was a huge, lengthy chapter that basically gives you the secrets of doing this Right. Rather than beating yourself up. And we’ve also talked about that this is the human genetic imperative to walk. I think you’ve covered a lot of that already. But I think it’s important to get into some of the, again, the evolutionary biology of how the homo sapien species operates and how bad it is to be seated for prolonged periods of time.

Mark (01:07:06):

Yeah. Well, for millions of years we evolved without chairs and tables and beds and sofas and we walked upright and we populated the earth walking, not running. We probably put in, I say we, our ancestors put in, who knows, 20, 30,000 steps a day, maybe less because they were trying to conserve energy, but they were always doing something, always moving, always lifting, carrying, building, climbing. But they weren’t sitting at with their bodies at a 90 degree angle. If they were sitting, they were cross-legged or they were doing all manner of different primal postures on the ground, whether it’s cross-legged, side legged.

Brad (01:07:47):

They were loading the skeleton,

Mark (01:07:48):

Squatting, they were loading the skeleton in different ways. So now we come to, you know, where we are today, which is, we’re kind of stuck in this lifestyle where there’s always a sofa to sit on, there’s a chair to sit on. We could have probably stood for this,

Brad (01:08:00):

why not ?

Mark (01:08:01):

Walk? Yeah.

Brad (01:08:02):

A walking podcast. But then you

Mark (01:08:03):

Get out and you, and then you decide you wanna run. Now you’re, you’re running almost at a disadvantage from the get go if you’ve been sitting all day, and then you’re, you run at the end of the day, or you go for a walk at the end of the day. You gotta have to, you know, stretch out and relax and realign your body so that your gait works on your behalf. And one of the key elements is this ground field, this ability of your feet to feel the ground underneath and to orchestrate the kinetic chain based on the input, based on the information that your feet get from feeling the ground. You can’t feel the ground in a thick cushion shoe. You have to either wear a minimal shoe or go barefoot. Talk about that a lot later in the book as well. But yeah, it’s imperative that when you do walk, you walk with good form.

Brad (01:08:46):